Condensation: What It Is, Why It Happens, and Why It’s Rarely a Window Problem

Summary

Condensation in modern homes is rarely a window failure and is instead a predictable outcome of high-performance, airtight architecture where humidity, temperature differentials, and ventilation strategies are misaligned rather than properly designed and managed.

Introduction

Condensation is one of the most common—and most misunderstood—conditions in residential architecture. Although it is frequently diagnosed as a window problem, it very rarely is.

At Dynamic Fenestration, our discussions around condensation rarely begin at schematic design. More often, they arrive later—after occupancy, after frustration, and after assumptions have already solidified into false conclusions. Windows are blamed, glass is questioned, and replacement is proposed.

That reaction is understandable, but it is very often incorrect.

Most of the time, condensation is not a failure of glass or windows, but is a symptom of an environmental and structural imbalance—between temperature, humidity, airflow, and how a building envelope actually behaves once it is sealed, conditioned, and lived in.

Understanding that distinction is the first step toward resolving the issue, whether that means adapting expectations, altering structural components, or designing differently to mitigate it before it appears.

Definition: What is Condensation?

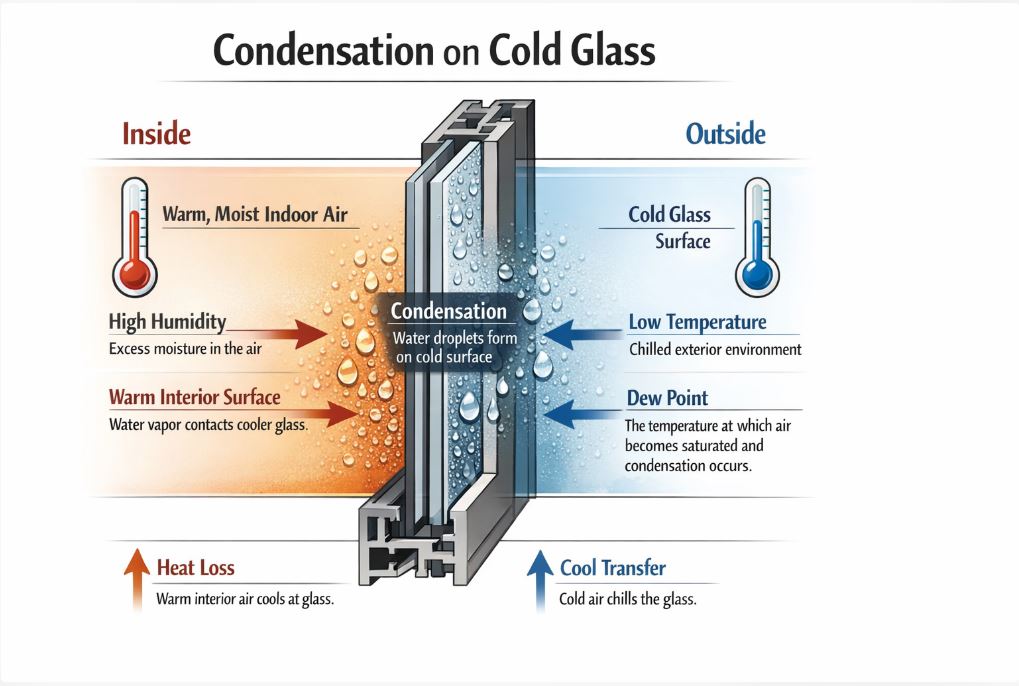

Condensation occurs when warm, moisture-laden air comes into contact with a surface whose temperature is at or below the dew point of that air. When the air can no longer retain its moisture, water vapor becomes liquid.

In residential buildings, condensation most often appears on glass because:

- Glass is typically the coldest surface in the room

- Modern architecture increasingly replaces opaque walls with transparent envelope

- High-performance glazing changes where temperature differentials occur, not whether they exist

The critical point: condensation forms primarily because of environmental conditions, not because a window has failed.

Reaction: Common Misdiagnosis

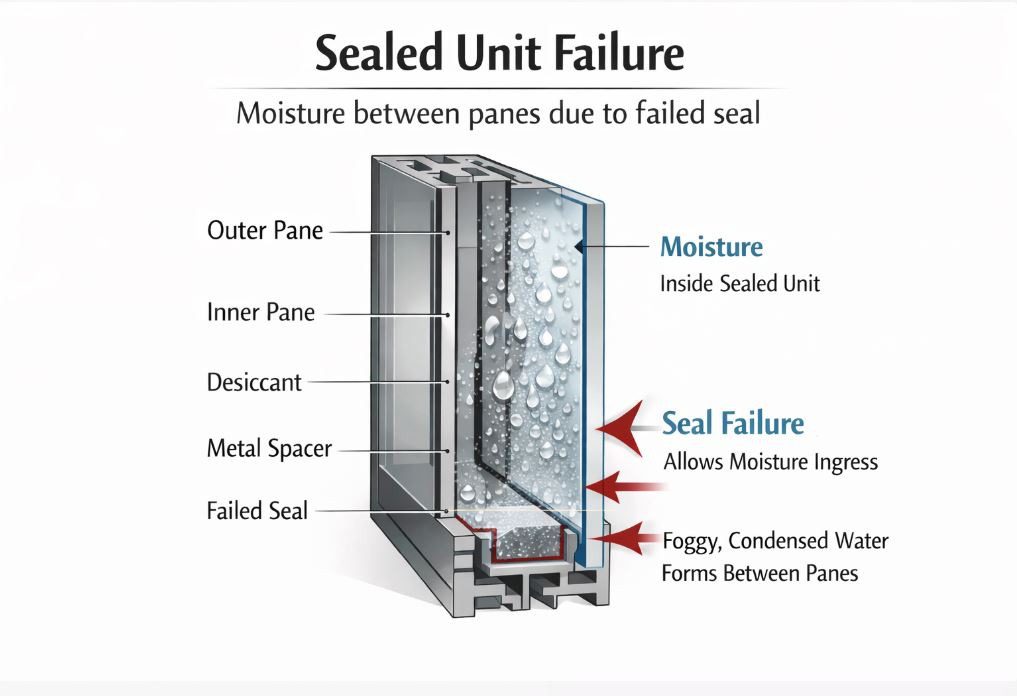

Despite these realities, when moisture appears on a window, people want to blame the window. This reaction is based on a persistent misunderstanding—the confusion between condensation and sealed unit failure.

They are not the same condition:

- Condensation appears on the interior or exterior surfaces of the glass and often changes with weather, occupancy, or HVAC operation.

- Seal failure presents as moisture trapped between panes and does not resolve with environmental shifts.

Replacing windows or glass units will not solve a condensation issue if the seal has not failed—because the glass was never the cause to begin with.

Situation: Why is Condensation More Common in Modern Homes?

High-performance architecture has rewritten the rules of building behavior.

Modern homes are:

- More airtight

- Better insulated

- Designed with significantly higher glass-to-wall ratios

- Increasingly reliant on mechanical ventilation rather than incidental air leakage

These are all positive advancements, but they also mean moisture has fewer unintended paths to escape.

Whereas older homes “breathed” by accident, modern homes must be taught how to breathe—intentionally, continuously, and correctly.

Without that calculated procedure, humidity will most certainly accumulate. And when humidity accumulates, condensation becomes inevitable.

Multiple Factors: What Causes Condensation?

Condensation does not have a single cause. It emerges from the interaction of multiple factors. Common contributors include:

- Elevated interior relative humidity

- Large interior–exterior temperature differentials

- Airtight construction without sufficient ventilation

- Inadequate thermal separation at openings

- Misaligned glass and coating specifications

- Orientation, exposure, and rapid diurnal temperature swings

This is where simplistic diagnoses fail. Condensation is never a one-variable problem.

A Practical Pause: How to Diagnose Condensation Correctly

Before blaming windows—or proposing replacement—condensation must be evaluated systematically. What follows is the same diagnostic logic we use internally with architects, builders, and envelope consultants.

Condensation Diagnostic Checklist: A Practical Tool

1. Identify Where Moisture Is Appearing

☐ On the interior glass surface

☐ On the exterior glass surface

☐ Between panes of glass

If moisture appears between panes, this indicates a sealed unit failure. But if moisture is on the glass surfaces, this is an environmental condition. Continue to step 2.

2. Confirm Interior Relative Humidity(RH)

☐ Measure actual interior RH (do not estimate)

☐ Compare RH to exterior temperature conditions

☐ Review humidification systems and seasonal settings

☐ Confirm occupants understand winter RH targets

High-performance homes often require lower winter RH than occupants expect.

3. Review HVAC and Ventilation Strategy

☐ Is the home mechanically ventilated (HRV, ERV, induced air)?

☐ Is the system balanced, commissioned, and operational?

☐ Are kitchens, baths, spas, and pools properly exhausted?

☐ Are HVAC setpoints extreme or inconsistent?

Airtight homes do not self-regulate moisture—they require deliberate ventilation.

4. Evaluate Airtightness and Interior Airflow

☐ Has blower-door testing been performed?

☐ Are there stagnant air zones near large-glazed areas?

☐ Is conditioned air circulating across glass surfaces?

☐ Are furnishings or detailing restricting airflow at windows?

5. Assess Glass and Coating Specifications

☐ Confirm glazing configuration (double vs. triple)

☐ Identify low-emissivity coating locations

☐ Verify alignment between glass performance and HVAC design

☐ Confirm specifications address climate—not just code

Higher thermal performance can shift condensation risk rather than eliminate it.

6. Review Frame Design and Thermal Separation

☐ Are window and door systems fully thermally broken?

☐ Are thermal breaks continuous through corners and interfaces?

☐ Are materials appropriate for climate and exposure?

☐ Are expectations aligned with material realities?

7. Inspect Installation and Surrounding Construction

☐ Is insulation continuous around the opening?

☐ Are thermal bridges controlled at structure-to-frame interfaces?

☐ Are air and vapor barriers properly integrated?

☐ Were installation details executed as designed?

Even exceptional systems fail when continuity is compromised.

8. Consider Orientation and Environmental Exposure

☐ Identify elevations with highest condensation occurrence

☐ Review solar exposure and shading strategy

☐ Account for rapid day–night temperature swings

☐ Consider proximity to water, pools, or coastal environments

9. Align Expectations Early

☐ Has seasonal condensation behavior been discussed?

☐ Are occupants educated on system operation?

☐ Is condensation framed as a performance signal—not a defect?

☐ Has an envelope consultant reviewed the risk holistically?

Final Diagnostic Principle:

If the checklist points to humidity, airflow, temperature imbalance, or envelope continuity, the issue is environmental—not fenestration failure. Remember, windows do not create condensation—they only reveal it.

Download the Free PDF Condensation Checklists and Guides Below

Condensation Checklist for Homeowners

Anticipation: How to Mitigate Condensation Risk

Condensation mitigation begins long before fabrication.

At the design stage, it requires alignment—between architecture, envelope strategy, glazing performance, and mechanical systems. At the specification stage, it requires understanding not just what materials can do, but what they cannot. At occupancy, it requires education.

Windows alone cannot eliminate condensation—they were never meant to.

Conclusion: How to Manage Expectations

Condensation cannot always be eliminated, but it can be anticipated, mitigated, and managed. The real failure is not condensation itself, but rather promising absolutes where physics does not allow them.

At Dynamic, we approach condensation the same way we approach fenestration: holistically. Not as a component problem, but as a system condition—where architecture, engineering, and lived experience intersect.

Remember, buildings create condensation—windows only make it visible. When that reality is acknowledged early, design intent is preserved, budgets remain aligned, and performance meets expectation. That’s not marketing—that’s responsibility.